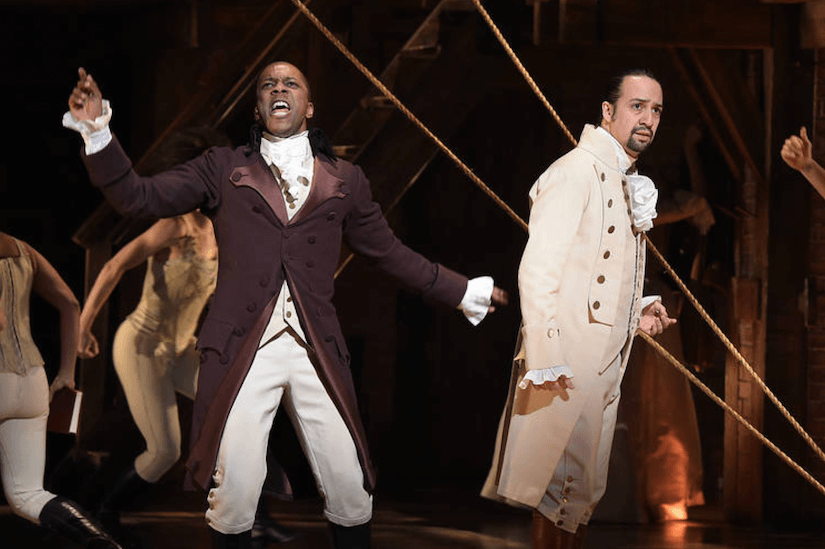

Left Leslie Odom, Jr. as Burr; Right Lin-Manual Miranda as Hamilton

The day my daughter and I got tickets to the Broadway play, Hamilton, it was by divine synchronicity.

A good friend, who knew I wanted to see it, heard that morning of two other friends who had tickets for that day’s matinee but suddenly could not attend. A couple of texts, a trip to the ATM, a quick handoff at Grand Central Station, a decision for my daughter to skip classes and there we were in our mezzanine seats, lapping up every note.

So I was really ready for the filmed version when it premiered on Disney Plus this weekend. Again, I found the production to be brilliant and deeply inspiring, particularly as I am working on an original production of my own.

This time I could see some of the performers’ facial expressions and subtle gestures up close in a way that was not possible to see in the theater. With the aid of my trusty remote, I could stop and rewind particular segments to more deeply examine the actor’s choices of movement or inflection, or listen more closely to a rapid-fire section of lyrics.

This has given me an even greater appreciation of the impressiveness of this work that is now indelibly part of the Broadway canon. Two observations, though.

Staging the founders of our country with colorblind casting, forces us to reframe our thinking about the foundation of this nation. In part, this has been challenging and refreshing.

However, it is also impossible to forget that these same founders were able to overcome the hypocrisy of declaring independence for themselves while holding other human beings as slaves. This has been widely debated since the play first aired on the July 4th weekend, and it will be fascinating to see the all-white version which will undoubtedly be performed somewhere one day.

But one element I have not seen discussed is the casting of the “villain” Aaron Burr as one of the darkest-hued performers. That, in contrast to the “hero” Alexander Hamilton and his family as among the lightest is very hard to ignore.

From lighter-skinned house slaves (those mixed with the master’s bloodline) receiving perceived preferential treatment to the darker field slaves; the brown paper bag and fine tooth comb tests of polite society later on, and the wide spread selling of bleaching creams on every continent on the planet even today, colorism continues to be an insidious element in our practiced notions of beauty, worth, equality and opportunity.

Renee Elise Goldsberry as Angelica Schuyler

Next, since the original cast of Hamilton left the Broadway run, I’ve enjoyed seeing many of them in other music, film and TV productions. Tony Award-winners Lin-Manual Miranda, Daveed Diggs and Leslie Odom, Jr., along with Chris Jackson, Okieriete Onaodowan and Anthony Ramos have most deservedly moved on to other career adventures.

But I’m most pleased that this new filmed version allows a wider audience to see what a powerhouse talent is Renee Elise Goldsberry. Maybe I’ve missed it, but I have not seen her benefit as greatly from her Tony Award-winning performance.

Watching the alchemy of breath, lungs and vocal cords, with intention, tone, pitch, notes, words and storytelling culminating in her deep and devastating portrayal is indeed a sight to behold. She gives a full-bodied performance, incorporating every ounce of herself, holding nothing back.

When she stands firmly onstage, throws her head back, holds out her arms and opens her mouth wide at the climax of the song Satisfied, I get chills.