From Sarah to A’Lelia – A Family Legacy

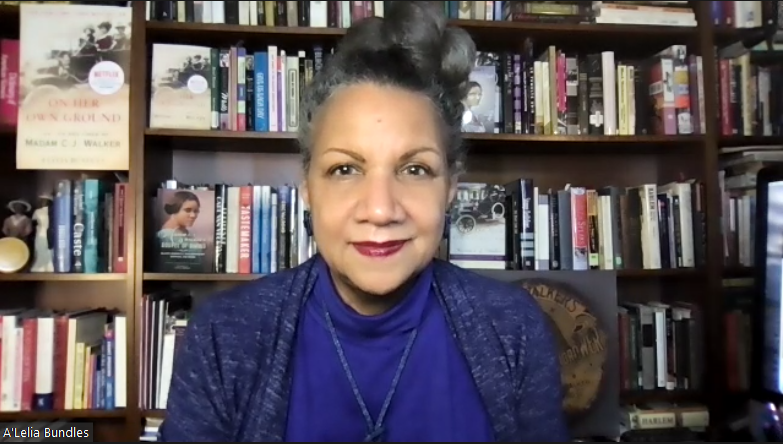

In honor of Women’s History Month, we’re celebrating a woman who has lovingly carried and promoted her family’s legacy for the benefit of the Culture. A’Lelia Bundles is a journalist, producer, and the biographer of Madam C.J. (Sarah) Walker, America’s first self-made female millionaire. Bundles is also the maternal great great granddaughter of Madam Walker. Her Walker biography, On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker, was the foundation for the Netflix series, Self Made, which was aired one year ago.

In this interview, Bundles makes clear that she was raised in tradition of civic-minded entrepreneurship from both sides of her family, and relates her experiences having her book turned into a Hollywood production.

Isisara Bey: It is said that a writer should write about what they know. Was that part of the impetus for you telling the story of Madam C.J. Walker? And why was telling this story important to you?

A’Lelia Bundles: I know the conventional wisdom is to write what you know. But I would also add to write what you learn, the things that we are exposed to and attracted to. The seeds for my telling this story were really planted in part because my mother went to work every day at the Walker company in Indianapolis and I would go with her to her office and I had memories of that.

But maybe even more so because her father, my grandfather who was born in 1892, was a great storyteller and knew his family history. He was married to my grandmother who was part of the Walker Company. But his grandfather had been elected to the state legislature during Reconstruction in Arkansas, his father had been valedictorian of his class at Lincoln in the 1880s, and his mother had gone to Oberlin. I didn’t know those things so I couldn’t write about those things without learning them. But I did have this sense of history as being something very different from what I learned in school.

Isisara: As descendants of Madam Walker, how did your family view her role and accomplishments within this larger society?

A’Lelia: One of the things that I think is really important about Madam Walker’s legacy is that she knew that her wealth came from within the Black community. She was specifically addressing the needs of African American women who were buying her products. So when she wanted to speak out on difficult political issues, when she wanted to advocate for her community in the anti-lynching movement, when she wanted to talk about women having the right to vote, she felt that she owed something to her community, not to people who were trying to circumscribe her. The larger community was more or less ignoring her until she started making money. They weren’t sanctioning her initially.

When she and her good friends, (crusader publisher) Ida B. Wells Barnett and Mary Talbert, who was one of the founding members of the NAACP, started talking about lynching and about the rights of Black soldiers during World War I, they were spied upon by a black spy in the War Department, who wrote them up in a report calling them “Negro subversives.” But Madam Walker was confident that it was her community who supported her, and she wanted to give back to her community.

When I was growing up, we didn’t sit around the dinner table talking about Madam Walker.

Yes, she became a millionaire, but more importantly, she provided jobs for thousands of African American women who then were able to buy homes and educate their children. At her 1917 convention, she really did have this sense of empowering women. She told the women, “Your first duty is to humanity. I want others to look at us as Walker agents and realize that we care, not just about ourselves, but about others.”

That spirit of political activism carried through into the 1960s when beauticians paid for the buses for people to go to the March on Washington For Jobs and Freedom.

Isisara: How was the sense of legacy passed down to you?

A’Lelia: When my mother and I would visit my grandfather in the apartment where he and my grandmother lived, I would go off into closets and drawers and find things that had belonged to Madam Walker and her daughter A’Lelia Walker and to my grandmother Mae. So I was discovering them before I had any idea who they were.

By going to my mother’s office with her I saw a woman in business and I saw the other women who worked in the factory. I got this sense that it was normal for a woman to be in business. My mother’s family had multiple generations of people in business. Both sides of her family had been entrepreneurs.

My dad’s family was different because his parents had migrated from Kentucky to Indiana as part of the wave of migration, and they were uneducated people, laborers. My paternal grandfather was a real hard worker, a real hustler. Even though he didn’t have great literacy skills, when he died he had more money in the bank than my grandfather who was a lawyer. My dad was pulling on that legacy of hard work and hustle, so I got the sense of a history of entrepreneurship combined with this sense of you are supposed to continue and to create your own legacy.

Isisara: MOWFF is launching a series of workshops for filmmakers, starting with writers. Can you speak a bit about how your biography of Madam Walker got to the film studio’s attention?

A’Lelia: When I was growing up, the last thing I thought I would be doing would be writing about Madam Walker, and talking about her life. In fact, when I was in high school, I wasn’t really very interested in history. I still got an A in the American History class, but it didn’t interest me because the only time Black people were mentioned was as slaves, and the books said that we were content. I had this really strong memory of being the only Black kid in the class, and reading that and just feeling horrible and unempowered.

When I went to graduate school my idea was to become a journalist and not to have really anything to do with the family business. But I was really lucky that Phyllis Garland, the only Black woman on the faculty at Columbia Journalism School, recognized my unusually spelled name.

Phil had been a reporter for Jet magazine, her mother had been an editor at the Pittsburgh Courier, and when Phil discovered my Walker family connection she said, “That’s what you’re going to write about.” So that is what set me on the path.

I graduated in 1976, and I met Alex Haley in 1982 when he was still on the wave of success from his novel Roots and wanted to do a mini-series and a book on Madam Walker. I ended up doing research for a project he was supposed to do. But Alex died without having completed it.

I wrote a young adult book, and then I wrote On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam CJ Walker, which was published in 2001. The book was optioned by Columbia Tristar (Sony Pictures), but that deal fell through. The executive who had optioned it got fired, so that was the end of that for a while. Then it was optioned a few years later by HBO, but the writer who was assigned to that project died.

Then the option came back to me, and we had that period of about a decade when the conventional wisdom in Hollywood was that nothing Black sells overseas, it’s not profitable and we’re not interested. And then April Reign, who I’ve never met but who changed things for all of us, created the #Oscarsowhite. Then 12 Years A Slave and Selma disrupted that conventional wisdom.

All of a sudden, I was getting emails and phone calls again,18 years later. Women directors were in demand, and women writers, so now I was having conversations with maybe three or four different producers and studios who were interested. I ended up going with someone who I thought really respected my work and would involve me in the process.

Isisara: How important is that respect in making the transition from book to script and film?

A’Lelia: It’s so important that the person who actually did the original research, and who pulled the material together, is respected. In my case, I happen to be a family member and so that adds yet another dimension.

Most of the time, once a studio or producer acquires a story, especially if it’s not a fiction story, they really wish you would go away. And the system, the structure has been set up so that that is what usually happens. They feel you’ll be interfering, you’ll be trying to whitewash the ancestor, you won’t let your precious words be changed. And I think that is a really very unenlightened way to look at it.

There are some more enlightened producers who see the value of having someone as a consultant who actually does know the material. In a biography, it’s not all going to end up on the screen. There have to be composite characters, things have to be conflated. But I appreciate it when I see something that I know the original writer has been included.

I just happen to have had an experience of being presented with a vision early on in the process where I thought I would have been included. Then I expressed an opinion that was different from the head writer and so I was excluded from most of the process. But I have had other experiences, and I’m in the process of working on other projects where I am respected and where my vision and my opinions are appreciated.

There’s so much opportunity for historians and biographers who have done this work, who have excavated these amazing stories of these powerful historical figures, to be able to work with people in Hollywood and in theater who really do want to tell these stories in their authenticity. With Judas and the Black Messiah, Fred Hampton’s wife and son were very much involved. You could feel it, and the intention of the director was there, too.

You can tell when someone is doing old Hollywood tropes. It’s really important that as Black people we try to resist the pressure to create and perpetuate stereotypes, and to not be thinking about the white gaze.

It is very difficult to produce anything in Hollywood because a lot of money is on the line. There’s an executive who ultimately has the power to say, “Well, why don’t you do it this way?” And there may not be any real logic other than it just feels easier to do a cliche. Robert Townsend’s Hollywood Shuffle is still the gold standard in a film depicting having to consider the white gaze.

Isisara: Can you name a couple of days that stand out for you in your experience as a writer of the source material for the Netflix mini-series, Self Made?

A’Lelia: There were some really positive moments for me to be able to actually see the story come to life on screen. It doesn’t matter whether I liked or didn’t like everything. The fact that it got made everyone tells me is a minor miracle.

Having Octavia Spencer in that role, every time she comes on screen I feel good. I feel that she’s the right person. She shows the tenacity, the perseverance, the dignity that I imagine Madam Walker had. I love the scene in the market where she’s trying to convince other women to buy her product, Octavia Spencer did this brilliantly.

I spent one day on the set and there were two scenes in particular that just blew me away because I’d never been on a film set. I worked in television news for a long time and I know you know how you shoot that. You can’t stage anything. In TV news you have to have that camera rolling and you hope that you capture what you need.

But there was one particular scene where Octavia Spencer as Madam Walker and Kevin Carroll as Madam Walker’s attorney FB Ransom were in her office, and they were discussing the fact that a made-up character had been lynched. The emotion that Kevin Carroll brought to that, and that he had to do it over and over again, was just stunning.

The other scene that was shot that day that just was great for me to watch. Octavia Spencer as Madam Walker and Blair Underwood as her husband C.J. Walker. First of all, it was just great to have Blair in there and to see him in action. What a nice, nice man he is. But this was a scene where she’s caught him with another woman. There’s some fireworks, and they were both incredible. It was just great to watch them do that over and over, the power that they brought to it.

And to be able to talk with the wig designers, the hairdressers, the makeup people, the set designers, people were so proud of the work they had done. Those are the memories I have from that one day on set.

Isisara: What advice would you give emerging writers about working in mainstream filmmaking? How should they prepare and protect themselves, their work product, and the intention and integrity of their ideas?

A’Lelia: You know, it is so difficult to protect your material and have it come out the way that you want it. And sometimes you’ve made compromises that you really don’t want to make. I think it’s really important to have a good lawyer. It’s really important to have an agent who advocates for you and who’s not afraid to speak up for you. Sometimes you have to say, “No, I’m not comfortable with what I think you want to do with my material,” and you have to be able to have the confidence and the courage to wait until the right situation comes along.

I know that there are people who have decided to do things on their own, to do their own productions, and sometimes that’s really what you need to do first. Even if it’s a small budget. Issa Rae is an example of that. And I’m seeing many more, especially younger people just deciding they’re going to do a low-budget thing and do it as well as they can, and then that becomes their resume. As opposed to a writer, selling the rights to their book and letting it just be put in the hands of someone who may not bring the same sensibilities to it.

And then there are other people who decide that they’re not going to do something that is a dramatic film. Stanley Nelson is an example of someone whose very first film documentary was on Madam Walker because his grandfather, F.B. Ransom was Madam Walker’s attorney. I remember when Stanley was working on that in the 1980s. I don’t know how much a reel of film cost then, but he would have to raise that money and then get the next thing, and so it took many years for that very first film to happen.

When I’ve talked with him about Two Dollars And a Dream, the documentary that he did on Madam Walker, and then comparing it to the Hollywood version with Self Made, I had the sense he just really wanted to be in control of his message. Now he has stuck to his guns and has created a generation of younger documentary filmmakers he’s nurturing, and a body of work on his own, an important body of work.

Isisara: Thank you, A’Lelia.