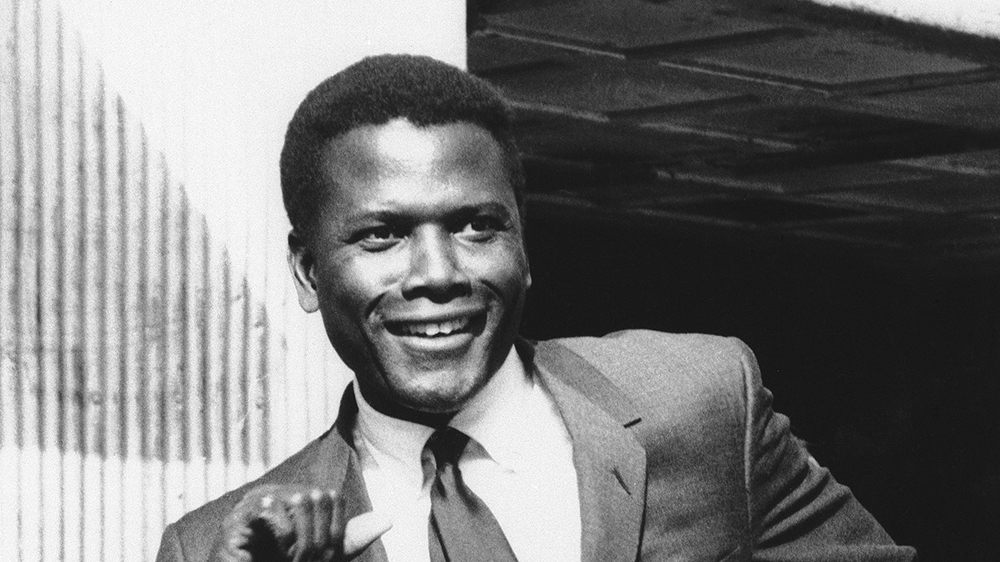

With the recent passing of Sidney Poitier, tributes and reflections have been pouring in for this man among men. I, too, have a Sidney Poitier story.

The year was 1992. I was a young mid-level executive at Sony Pictures Entertainment in Culver City, CA. That was the year that the American Film Institute gave Mr. Poitier a Life Achievement Award. Columbia Pictures, part of Sony Pictures Entertainment, had good reason to celebrate the recipient and the honor.

For the decade of the 60s, Sidney Poitier’s films were the studio’s economic driving engine. A veritable money machine. Between 1961 and 67, one hit after another – A Raisin in the Sun, Lilies of the Field, A Patch of Blue, In the Heat of the Night, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner – stormed the box office and racked up nominations and awards.

Those were the days when Mr. Poitier was most likely the only African American in his studio meetings, or walking across the lot, or filming on the sound stages. To paraphrase the quote, he did not ask for a lighter burden, but for broader shoulders, and he strode with the cadence of a king.

As was the custom when a studio’s major star was honored, Columbia Pictures’ was first among equals in contributing a substantial sponsorship for the awards ceremony which included a couple of tables, front and center, at the banquet. The studio then invited company executives and industry guests to populate the tables in support of the honoree.

There were a small handful of African American corporate executives in the company. We were all excited and thrilled for Mr. Poitier because of all that he meant to us as a race of people. We were disheartened in equal measure to learn that none of us was invited to witness Mr. Poitier receive the award. Within the studio “family,” it was not even considered that we were especially connected to him, nor him to us.

So the highest-ranking brother on the lot at the time, Bob Holmes, drafted a letter to Mr. Poitier that a group of us co-signed – Bob, Darrell Walker, Harvey Lehman, Harold Pierce, Debra Martin Chase and me.

In it, we expressed our love for him, our pride in his achievement, our gratitude for all his accomplishments as an actor, director, political activist and human being. Mr. Poitier represented all of us. He knew it and we knew it, and under the weight of a million expectations, he never let us down.

Not long after the letter was sent, I was in my office when the phone rang. I answered and heard a voice say, “Miss Bey, will you please hold for Mr. Poitier?”

And then there he was, with that warm, sonorous voice quickly recognizable from stage and screen. He expressed how deeply touched he was to have received our letter, how much it meant to him, that he had framed it and looked forward to reading it again and into his twilight years.

We now know that Mr. Poitier took the time throughout his life to touch thousands of people with a one-on-one acknowledgment of some kindness he received. These small gestures and thoughtful moments were his private gifts to us. We were not stars, just everyday folk who had the great fortune of crossing paths with this unforgettable giant of a man.